Let’s Respond to The Quiet Revival

Quiet Revival and the Next Generation

You can watch Tim Alfords’ presentation on the changes we need to make to reach the next generation here: Watch on YouTube or Download the slides as a .zip

The Bible Society’s phrase Quiet Revival names a sociological shift: churchgoing and Scripture engagement are rising after years of decline, with young adults a surprising part of the story. For Tim Alford, that’s less a headline than a summons. “God is doing something in this generation right now,” he says. The question is how churches should respond.

Alford’s answer is not a new program but a reorientation—toward encounter, toward family, and toward priority.

“We actually robbed Christianity of the very thing that makes it so compelling in the first place, which is the presence of God.”

Words to Power

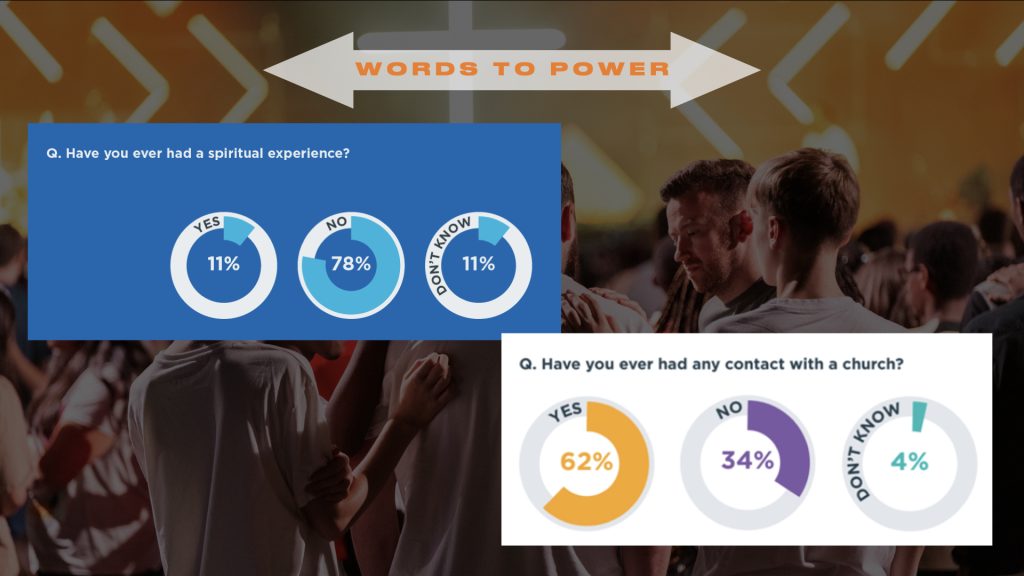

He argues that a long season of anxiety about appearing “weird” has left many services heavy on explanation and light on expectation. That instinct, he says, lands exactly wrong for a cohort that is spiritually inquisitive but institutionally wary. Young people are not afraid of the supernatural; they are searching for it, often outside church. If that’s the landscape, then gatherings need space where people can meet God, not merely hear about Him. Tim’s provocative claim is we need to see an end to the ‘seeker friendly’ church model

He argues that a long season of anxiety about appearing “weird” has left many services heavy on explanation and light on expectation. That instinct, he says, lands exactly wrong for a cohort that is spiritually inquisitive but institutionally wary. Young people are not afraid of the supernatural; they are searching for it, often outside church. If that’s the landscape, then gatherings need space where people can meet God, not merely hear about Him. Tim’s provocative claim is we need to see an end to the ‘seeker friendly’ church model

Alford reaches for the Apostle Paul’s frame—“not with wise and persuasive words, but with a demonstration of the Spirit’s power”—and applies it to ordinary Sundays: longer room for worship and response, prayer for healing and freedom, time to listen and minister. The aim is a faith that rests “on God’s power,” not only on human wisdom. He even borrows Justin Brierley’s provocation for this cultural moment: “Keep Christianity weird. Embrace mystery. Expect the supernatural.”

Organisation to Family

The second move is cultural rather than programmatic. “If the church is to help the next generation find and follow Jesus, we must build on the principles of family rather than business,” Alford says. “In a business we hire and fire employees; in a family we raise sons and daughters.”  He points to the New Testament’s parental language—Paul writing “my child” to Timothy and Titus—as a template for spiritual parenting over managerial throughput. In practical terms, that shifts Sunday decisions and leadership habits: belonging before performing, mentoring before metrics, younger voices at the table before they are perfect.

He points to the New Testament’s parental language—Paul writing “my child” to Timothy and Titus—as a template for spiritual parenting over managerial throughput. In practical terms, that shifts Sunday decisions and leadership habits: belonging before performing, mentoring before metrics, younger voices at the table before they are perfect.

His shorthand parable is homespun: a dad suggests action classics for movie night; the child picks The Lion King again. In a healthy family, the older generation gladly yields. Translated to church life, the point is plain. If we really are a family, songs, sermons, formats and serving should reflect the needs of the young, not only the preferences of the old. “We’ve got to stop just using the language of family,” he says, “and start acting like it.”

After-thought to First-Thought

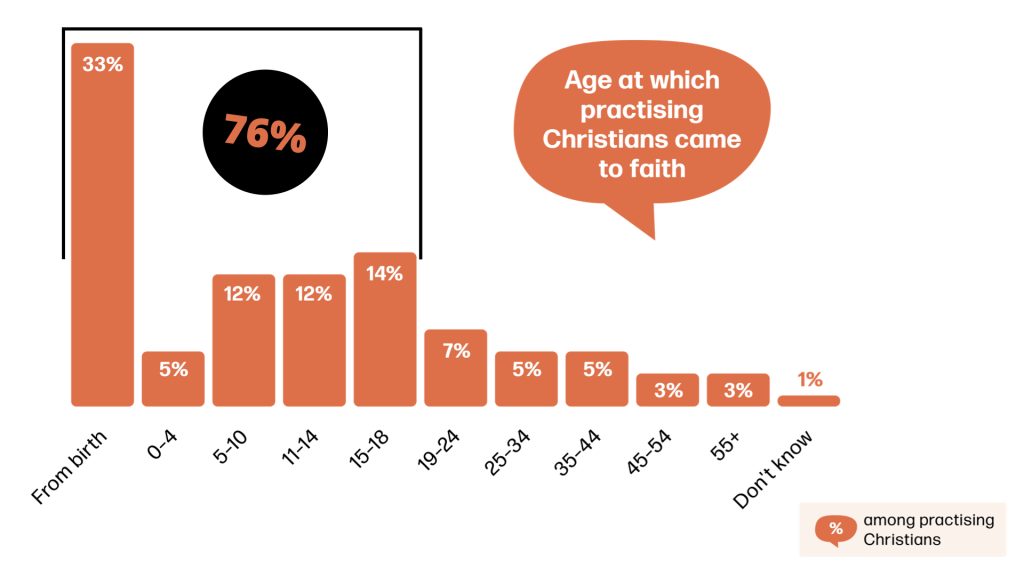

The third shift is strategic. Research consistently shows that most lifelong Christians first responded to the gospel in childhood. If that’s where enduring discipleship usually begins, Alford asks, why do leadership time, budget and creative energy so often flow elsewhere? “Put the first and best of our resources, creativity and people into kids and youth,” he says. It is not an add-on but the front line—schools work, midweek outreach, age-appropriate discipleship, and, crucially, seasoned pastors and gifted communicators serving there by design, not by default.

The thread running through all three moves is encounter. “Personal relationship with God is born out of personal encounter with God,” Alford says. Within the Quiet Revival frame, the counsel is old and bracing: welcome the Spirit’s power without embarrassment, recover the ordinary bonds of family, and place the youngest at the center of the plan rather than the edges of the budget.

If this moment truly is a quiet revival, the work ahead is neither quiet nor novel. It is the work of a people willing to be spiritually serious, relationally familial, and strategically focused—so the next generation can find and follow Jesus in the church they inherit.

Related posts

MOVEMENT – January 2026 - BOOK A SEAT IS ESSENTIAL: https://www.trybooking.com/uk/FVNT We’re back! After successfully gathering 300 young people in the last two gatherings, we’re keen to come together again. This is MOVEMENT, named by young people at Together Festival – a moment to worship, pray and gather the young people of our region. We are calling young people who love Jesus […]

MOVEMENT – January 2026 - BOOK A SEAT IS ESSENTIAL: https://www.trybooking.com/uk/FVNT We’re back! After successfully gathering 300 young people in the last two gatherings, we’re keen to come together again. This is MOVEMENT, named by young people at Together Festival – a moment to worship, pray and gather the young people of our region. We are calling young people who love Jesus […] Let’s Respond to The Quiet Revival - Quiet Revival and the Next Generation You can watch Tim Alfords’ presentation on the changes we need to make to reach the next generation here: Watch on YouTube or Download the slides as a .zip The Bible Society’s phrase Quiet Revival names a sociological shift: churchgoing and Scripture engagement are rising after years of decline, […]

Let’s Respond to The Quiet Revival - Quiet Revival and the Next Generation You can watch Tim Alfords’ presentation on the changes we need to make to reach the next generation here: Watch on YouTube or Download the slides as a .zip The Bible Society’s phrase Quiet Revival names a sociological shift: churchgoing and Scripture engagement are rising after years of decline, […] Next Gen Leaders’ Gathering - As part of our investment into the Next Generation, we continue to network and facilitate relational unity between kids and youth workers across the region. On Monday 22nd September, we are hosting a gathering for those involved with leading and working with children and young people in any capacity. We will pray, worship and share […]

Next Gen Leaders’ Gathering - As part of our investment into the Next Generation, we continue to network and facilitate relational unity between kids and youth workers across the region. On Monday 22nd September, we are hosting a gathering for those involved with leading and working with children and young people in any capacity. We will pray, worship and share […] Responding to the Quiet Revival - An Evening for Church Leadership Many of you will have seen the Sunday Express’s front page headlines published on the 27th July; ‘GLOBAL CRISIS SENDING GEN Z TO CHURCH’. The Express is one of many national news outlets reporting the spiritual shift taking place in our nation among Gen Z. The Bible Society report that […]

Responding to the Quiet Revival - An Evening for Church Leadership Many of you will have seen the Sunday Express’s front page headlines published on the 27th July; ‘GLOBAL CRISIS SENDING GEN Z TO CHURCH’. The Express is one of many national news outlets reporting the spiritual shift taking place in our nation among Gen Z. The Bible Society report that […] Next Gen Leaders’ Gathering - As part of our investment into the Next Generation, we continue to network and facilitate relational unity between kids and youth workers across the region. On Monday 2nd June, we are hosting a gathering for those involved with leading and working with children and young people in any capacity. We will pray, worship and share […]

Next Gen Leaders’ Gathering - As part of our investment into the Next Generation, we continue to network and facilitate relational unity between kids and youth workers across the region. On Monday 2nd June, we are hosting a gathering for those involved with leading and working with children and young people in any capacity. We will pray, worship and share […]